by Jane Seigler, Chair of MHC’s Government Relations Committee (first published in the July 2022 Equiery)

For most of its history, the Preakness, the second jewel in the Triple Crown, has called Baltimore its home. For much of recent history, as was noted by Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott in a Baltimore Sun Op-Ed, the event – while hugely important to Baltimore’s culture, history and economy, “was held within Northwest Baltimore, but not with the community of Northwest Baltimore.” That changed this year.

This year, Park Heights Renaissance, a nonprofit dedicated to restoring the Park Heights community surrounding the Pimlico Race Course, organized a companion festival on Preakness Day, honoring the legacy of African Americans as part of the state’s equestrian history.

The George “Spider” Anderson Preakness Music and Arts Festival was held in Park Heights just a few blocks from Pimlico, occupying a 17 acre site currently slated for re-development. The Festival not only paid tribute to Anderson, the first African American jockey to win the second jewel of the Triple Crown in 1889, but also focused on highlighting both the Preakness and the history of people of color in the racing industry.

It is an often overlooked fact that, for most of the early years of Thoroughbred racing in America, African-American jockeys dominated the sport. As chronicled by The Equiery in the May 2021 issue: “In the first Kentucky Derby (1875), for example, 13 of the 15 jockeys were African American and out of the first 28 runnings of the Derby, 15 were won by African Americans. These first professional African American athletes included Isaac Burns Murphy, who many in the industry consider one of the greatest American Thoroughbred jockeys of all time. Murphy earned 628 wins from the 1870s through early 1890s and logged 37 major racing wins during his career, including winning the Kentucky Derby three times (1884, 1890 and 1891).”

George “Spider” Anderson rode Buddhist to victory in the 1889 Preakness Stakes. Again, per the May 2021 Equiery, “A native of Baltimore, Anderson rode in his first race in 1883, when he was just 12 years old. Within three years, T.B. Davis and Frank Hall hired him to ride horses they had stabled at the Ivy City Colony in Maryland. He went on to ride for such prominent owners as August Belmont, D.D. Withers, William L. Scott, Bryon McClelland and William “Bill” Daly. Anderson also crossed over into the Steeplechase racing scene, riding such horses as Bess, Councellor Howe and Sir Vassar to wins from 1889 to 1897. After retiring as a jockey, Anderson stayed with the sport as a co-owner in several racehorses.”

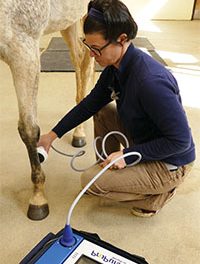

His eponymous Festival in its debut this year featured music, arts and crafts, live streaming of the races, and food trucks, but a big attraction was the area organized by MHC-member City Ranch, a nonprofit run by MHC Vice President Ahesahmahk Dahn, that is “dedicated to providing accessible and affordable horseback riding that develops positive character in children through the joys and responsibilities of horsemanship.” City Ranch serves Baltimore City and surrounding counties with lessons, workshops, therapy riding and horse care. City Ranch also sponsors the all-Black Charm City Polo Club. Dahn says that City Ranch “bring[s] horses to neighborhood events so children and their families have an opportunity to meet these gentle and sensitive creatures.”

The City Ranch presentation at the Festival included talks about African-American contributions to America’s equestrian history, including not only racing but also the Buffalo Soldiers. Mr. Michael Theard, President of the 9th and 10th Horse Cavalry of the Buffalo Soldiers, was on hand with uniforms and tack exhibits, and with a fascinating historical talk. Although several African-American regiments were part of the Union Army during the Civil War, the “Buffalo Soldiers” were established by Congress in 1866 as the first peacetime all-black regiments (the 9th and 10th Calvary Regiments) in the regular U.S. Army. In the early years, they were composed of black enlisted soldiers commanded by white commissioned officers and by black noncommissioned officers. The first black commissioned officer to lead the Buffalo Soldiers and the first black graduate of West Point was Henry O. Flipper in 1877.

The Buffalo Soldiers played significant roles in the history and development of the Southwest and Great Plains, fulfilling not only military roles in campaigns against Native American tribes and in conflicts between farmers and ranchers, but also helped build roads, and escorted the US Mail. Into the early part of the 20th century, the Buffalo soldiers served in the Spanish American War (1898), the Philippine-American War (1899 – 1903) and the 1916 Mexican Expedition. Before the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916, Buffalo Soldiers also were deployed in Yellowstone and Sequoia National Parks, to protect against illegal grazing, poaching, timber theft and forest fires. Because their riding skills were considered to be superior, Buffalo soldiers taught riding, mounted drill and cavalry tactics at West Point from 1907 to 1947.

By the start of World War II, the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments were mostly disbanded, and in 1948, President Truman signed an Executive Order desegragating the military.

Dahn and City Ranch also brought some of the players from their Charm City Polo Club, who provided a scaled down demonstration game. The biggest hit was pony rides. Scores of families lined up all afternoon for pony rides, skillfully managed by City Ranch’s experienced staff (human and equine), who handled the unusually hot day with aplomb. WBAL’s Kim Dacey also stopped by to interview participants.