March 2006

At press time, the outbreak of equine herpesvirus (EHV-1, or “rhino”) that began Jan. 2 and claimed the lives of four Maryland racehorses appears to be on the wane at local tracks. Since late January, however, two event horses at a private farm near Worton, on the Eastern Shore, have been euthanized due to the virus.

In addition, according to the Maryland Department of Agriculture, test results returned Feb. 16 on 37 horses in a barn at the Fair Hill Training Center yielded 10 positive results. But at this writing, none of the horses have exhibited signs of the virus’ dangerous neurologic form, MDA officials say. The same is true of two horses that developed fevers in Laurel Park’s Barn 9 the second weekend in February. According to the MDA, neither horse has demonstrated neurologic symptoms, and the one who initially tested positive for EHV-1 had tested negative by Feb. 17.

Stopping the Spread

EHV-1 causes upper respiratory infection and fever and can also cause mares in foal to abort. But in its most dangerous form, it attacks the nervous system and can lead to paralysis or death. Horses who survive this neurologic form of the virus do not always recover completely. As there is currently no known method to reliably prevent this form, containment is crucial while the virus runs its course.

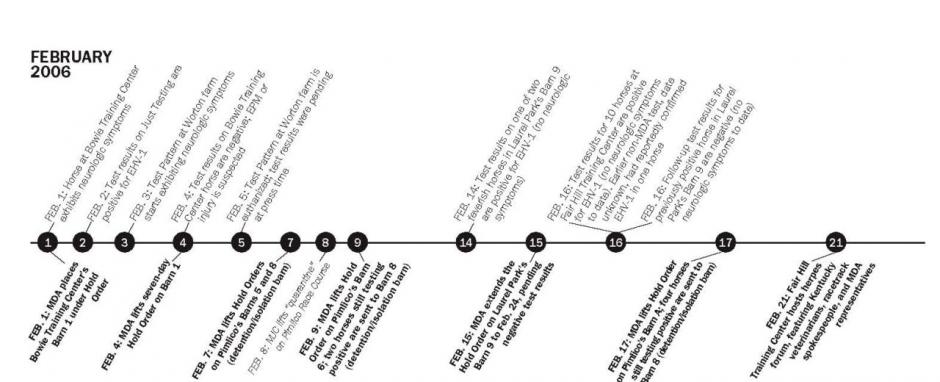

The outbreak in question, which took the neurologic form, erupted just after the New Year at Baltimore’s Pimlico Race Course. On Jan. 5th, MDA placed (on Pimlico’s Barn 5) the first of what would come to be several “Hold Orders” at Pimlico (see sidebar for the definition of a Hold Order). By Jan. 25, three horses – two on the newer side of the track, and one on the older side – had been euthanized due to the effects of EHV-1. Eventually, MDA Hold Orders were placed on all the affected barns (Barns 5, 6, A and Barn 8, the detention/isolation barn – see timeline graphic), with the sick horses isolated and treated, and protocols for viral containment observed. According to the MDA, each horse in a barn under a Hold Order became eligible for release 21 days after the last clinical case in that barn, pending his or her negative test results.

The Maryland Jockey Club (MJC) elected to “quarantine” (see sidebar for definition of “quarantine”) the entire Pimlico facility on Jan. 21. The decision was reportedly spurred in part by the news that a horse from Pennsylvania’s Penn National, who had run at Laurel Park the same day as Pimlico’s second fatal EHV-1 case, had since tested positive for the virus. But with no new cases since Jan. 19, the self-imposed “quarantine” was lifted on Feb. 8.

This meant that horses from Pimlico’s unaffected barns were now free to resume racing at Laurel Park, a source of relief to horsemen whose livelihoods depend upon it. (At this writing, however, racing at Laurel Park has been limited to horses from Laurel, Pimlico, Bowie and private farms, as outbreaks here and in Kentucky have prompted tracks in other states to restrict movement to and from their facilities. Given the outside restrictions and the shortage of entries, two major stakes races and some Sunday racing at Laurel have also been canceled. ) The Hold Orders on Pimlico’s Barns 5 and 6 were released on Feb. 7 and 9, respectively, with the two Barn 6 horses that were still testing positive sent to Barn 8 (the detention/ isolation barn, which had also cleared Feb. 7).

On Feb. 17, the MDA lifted the Hold Order on Pimlico’s Barn A after 21 of its 25 horses tested negative for EHV-1. The four horses from Barn A that did not clear the testing process were sent to Barn 8, the detention/isolation barn, and along with the two others from Barn 6 who hadn’t cleared the previous week, were prohibited from contact with other horses until they tested negative.

“Lifting the last remaining Hold Order at Pimlico is a positive [sign] that things are coming to a close there,” says Maryland State Veterinarian Guy Hohenhaus. “We will continue working with all parties involved to monitor the situation and bring it to a conclusion. We thank the owners, trainers and staff for their diligence in practicing prudent bio-security measures and their patience as we work through this science-based process that will make sure the remaining horses test negative before they will be released from the detention barn.”

On Feb. 18, Pimlico returned to normal training hours (6-10 a.m.) and each horse stabled on the grounds (except the six in the detention/isolation barn) was allowed to race at Laurel Park.

Meanwhile, at Laurel Park, Barn 9 remained under a Hold Order until Feb. 24, pending negative test results. A filly there was euthanized Jan. 26 due to a suspected pelvic injury, but was later found to have contracted EHV-1. The weekend of Feb. 11/12, two horses in that barn reportedly developed a fever, with one subsequently testing positive for EHV-1 and prompting the extension of the existing Hold Order. On Feb. 17, however, follow-up test results came back negative on both horses, and neither has “gone neuro” by press time. In addition, a suspected case of herpes at Bowie Training Center has tested negative.

“Given that Pimlico has been new casefree for the better part of a month now, that’s pretty encouraging,” Hohenhaus says. “That starts to suggest that it’s burning itself out – and likewise for Laurel.”

Beyond the Racetrack

But elsewhere, EHV-1 still seems a clear and present danger. Two of the virus’ most recent casualties occurred at the property formerly known as Seven Hills Farm, a boarding and training facility near Worton operated by noted event rider/trainer Kim Meier-Morani.

On Jan. 10, Meier-Morani received a yearling filly that came from the Ocala, Florida sales – by way of Pimlico – to be broken. At the time of the filly’s layover at Pimlico, officials believed that the herpes virus was limited to the opposite side of the track, and traffic to and from Pimlico was still permitted.

Five days after the filly arrived at the farm, Meier-Morani says she got “the snots.” But since she wasn’t running a temperature, the horsewoman says she wasn’t particularly concerned. In addition, she says that all of her horses are vaccinated against flu/rhino three times a year (in February, May and August, during peak travel times). “If you don’t know what [the neurological form of the virus] does, you’re not particularly worried about it, because you figure ‘Hey, I gave a shot against it, I’m okay,'” she says.

Then, on Jan. 19, Meier-Morani received word that a horse in Pimlico’s Barn A – the barn in which her new arrival had stayed – had tested positive for the virus. Although the outbreak had been featured in news reports around the state, Meier-Morani says she was unaware of it until that night. The next day, she had six horses with temperatures, three of them high.

Hohenhaus, who placed a Hold Order on the Meier-Morani farm on Jan. 26, says that the situation there isn’t as easy to manage as individual racetrack barns, where horses are stallbound most of the time. “The horses [at the Worton farm] are commingled a large number of hours a day in pens and paddocks, and have fenceline contact,” he explains. “So while there are two separate barns, there aren’t two separate populations of horses, from a disease control standpoint. We had no choice but to consider all of them as exposed.”

Since her experience with EHV-1 began, Meier-Morani says she’s learned that although there are conflicting schools of thought on the efficacy (and even the advisability) of repeat vaccinations on the virus’ neurologic form, many vets recommend that the flu/ rhino vaccine be given every 90 days – i.e., four times a year. She has also learned firsthand about the devastation the neurologic form can cause, having nursed two cherished homebreds – full sisters, in fact – through the heart-wrenching final hours of their lives. One was her daughter’s 5-year-old Pony Club mount Just Testing, who was euthanized Jan. 26. The other, Test Pattern, was a 7-year-old Preliminary eventer and consistent ribbon winner who belonged to Meier- Morani’s friend Susan Newton-Rhodes. She was euthanized Feb. 5.

At press time, Hohenhaus says the Worton farm has been infection-free (by the MDA’s definition of that term) for about 10 days. However, Meier-Morani was still monitoring two horses impacted by the virus: the homebred Test Ride and her full sibling, Meier-Morani’s beloved upper-level event horse Test Run. Tenth at the 2004 Rolex Kentucky CCI****, he also completed the 2004 Burghley CCI**** with Meier-Morani in the irons. “I have a four-star horse it took me my whole life to breed and develop,” she says. “And he can’t trot now.”

Minimizing the Risk

At press time, Hohenhaus says officials were still trying to determine the status of interstate health papers on the filly from Florida that ended up at Meier-Morani’s farm. The filly has reportedly recovered from the virus.

Did she pick up EHV-1 in Florida, at Pimlico, or somewhere in between? “It’s hard to say,” he admits. “[Florida officials] are telling our folks that they haven’t had any problems anywhere. So is it possible that an 18-hour trailer ride caused herpes to emerge in that horse, and then it dropped off a present at Barn A on the way through? That’s certainly possible.”

As Hohenhaus explains, EHV-1 – which isn’t as contagious as, say, influenza – lies dormant in many horses until activated by unknown triggers (some experts believe stress might play a role). “Why exactly it wakes up in that vicious form is not at all understood,” he says. “I’ve always had at least a partial suspicion that the Barn A outbreak was separate and distinct from what was going on at the other side of Pimlico. It could just as easily be directly linked, but the circumstances suggest that it might be … an unfortunate coincidence in time.

“But when the dust settles and the herpes season is behind us in a couple of months, [Gluck Equine Research Center in] Kentucky is going to attempt to do more detailed fingerprinting of the samples that we’ve sent them,” he continues. “That allows us to compare viral types between barns and between individual horses.”

Meanwhile, Hohenhaus says that while the current flu/rhino vaccine is no panacea, it’s still best to administer it every 90-120 days. Some experts believe that routine vaccination might reduce the respiratory form of EHV-1 infection, which in turn might help prevent the neurologic form.

In terms of general hygiene, Hohenhaus recommends avoiding shared tack and handling, “particularly anything that has to do with the front of the horse, including the handlers’ hands, bits and bridles, and identifiers at the tracks.”

In addition, he says, “If the horse doesn’t need to go somewhere, don’t take him. On the other hand, if you have strange entries to your population, you really need to segregate them for, ideally, 21 days. But even a week is a huge benefit … and that’s just basic good husbandry.

“But you can’t get the risk to zero,” he emphasizes. “You have to accept the fact that if you’re going to do with your horse what you would like to do with it – whether it’s race it, ride it or show it – you’re going to have to accept some risk.”