By Katherine O. Rizzo (first published in the July 2020 Equiery)

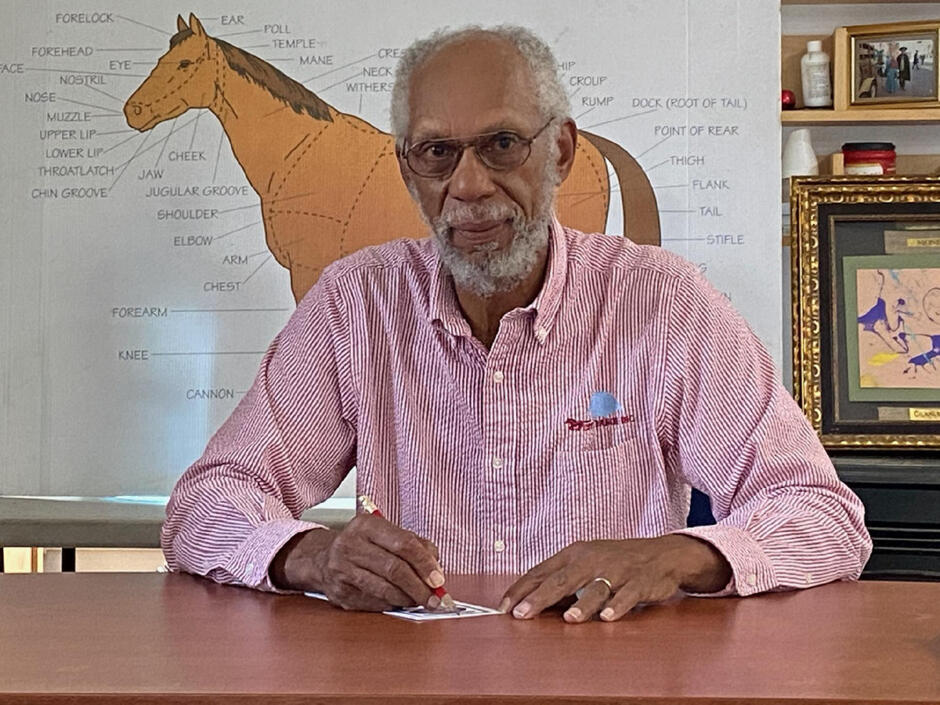

Ahesahmahk Dahn is moving towards transitions: transitions at The City Ranch, which he founded in 2007, transitions through the Maryland Horse Council where he serves as Treasurer and member of the Executive Committee, and transitions within the country’s equine industry where people of color are scarcely seen in leadership roles. As the 73-year-old Dahn begins to slowly plan his retirement, being part of these transitions is at the top of his list.

Becoming a Leader

Dahn was born in South Carolina but has spent the majority of his life in Baltimore City. His parents split up in the 1950s and Dahn moved to Baltimore with his mother. “My mother comes from a very large family that was spread around the country. She had a sister in Baltimore so that’s where we went,” he stated. “I was around 10 years old and the schools had just become desegregated.”

Dahn attended an integrated elementary school before moving on to an integrated middle school, but said “It just did not work out well.” He transferred to Douglas High School where he found his niche as a star athlete. Dahn earned a basketball scholarship to Morgan State University in Baltimore where he also played on the school’s 1965 championship football team.

While in college, Dahn advanced through the ROTC program and enlisted in the U.S. Army, commissioned as a Second Lieutenant, during the Vietnam War. He graduated from Morgan State in 1970 with a degree in accounting, and said “I was blessed that I was never called up [for Vietnam].” After the Army, Dahn went to work for Union Carbide, traveling the country learning every part of the vast company. “I realized that accounting was not my schtick and moved into industrial sales which met my personality better,” he said.

He spent some time in New York and New England where he sold welding equipment and specialty gasses, but then the “economy went south and my position was considered excess,” he explained. Dahn, who gravitates towards leadership roles, started his own specialty advertising business but shortly after, decided corporate America was just not for him.

“I come from a family of educators and at the time, teaching became a more valuable idea,” he said. Dahn had recently gone through a divorce and his son, Moshe, would spend the school year with his mother and the summers with him. “Teaching allowed me to be home when he was home, which was important for me,” he added. Dahn taught elementary school for a few years but felt the leadership at the school was “lacking.”

From there he became the Director of Facilities at Florence Crittenton Services of Baltimore, Inc., a residential program for single women with children, and stayed there for 10 years before the program shut down. Dahn was also a sailing instructor for the Downtown Sailing Center, a Baltimore non-profit that introduces inner city kids to the sport of sailing. He also once ran a paper route for The Baltimore Sun and through it all, had an interest in horses.

Let Them Run

It was a cold day in western Wisconsin when Dahn went for a ride with one of his brothers. “We went to ride some horses this guy was selling and were moving on at a pretty good clip and so I said to my brother, ‘we better ease up so we don’t hurt these horses,’” he explained. “Well the guy who owned the horses said ‘no let them run!’ and man did we run! It was like a dream.” Dahn was first introduced to horses as a child at his uncles’ sharecrop farms where mules were used to plow fields, and in his teens held a summer job at Nixon’s farm just outside of Baltimore City.

He always wanted to have a horse of his own and bought one of the horses from that Wisconsin ride. Next, he made arrangements to borrow a trailer to drive the horse from Wisconsin to New Hampshire where he was working at the time. “Well, the horse never made it,” he said with a chuckle. “You see, I was driving out there in a snow storm and the trailer flipped over. There was no horse inside at that point but after getting the trailer fixed, I just decided it was best to leave the horse out there!” Dahn has no regrets, as his brother and nephew ended up enjoying riding the horse for years afterwards.

It was not until much later that Dahn attempted horse ownership again. He was back in Baltimore City, married to Vivian Jean B. Dahn and the father of two, son Moshe and daughter Julia. “I kept talking about wanting a horse and one day my wife just said ‘then go get a horse,’” he said. So he did. A yearling named Libby that Dahn spent a lot of time working in hand before admitting to himself that he needed some professional help with the young horse.

“So I sent him off to a trainer for a few months and you know what? I get the horse back and on that first ride he bucks me off and I ended up in the hospital,” Dahn said with a laugh. Dahn ended up with “not too serious” injuries but never gave up on that horse or his love of horses.

The City Ranch

The idea for The City Ranch stems from a family tragedy in which one of Dahn’s nephews, who was involved at a very low level in the City’s drug trade, was killed. “I started asking myself, what am I doing here? How can I help get kids out of gangs, out of drugs and move them towards a more positive life?” he said. Thus, City Ranch was born.

According to City Ranch’s website, the program’s mission became to “develop positive character in children through the joys and responsibilities of horsemanship, and to bring horseback riding to the urban environment.” City Ranch started by bringing horses to inner city Baltimore schools. “We kept our horses at the farm but would trailer them to the schools,” Dahn explained. “And from the moment we park the trailer, the kids are involved in learning every aspect of horse care, from unloading the horse to grooming and eventually to riding.” The fully mobile program brings everything needed to teach horsemanship and riding to each school, including a round pen!

Many members of his family support the program, which Dahn describes as “a family thing.” Dahn himself is an unpaid employee, and he wants to remain unpaid so that those he mentors, who are now stepping up into leadership roles, can be paid. “I want to make sure my staff is taken care of,” he explained. Christopher Griggs is one such staff member who is taking up more of the reins of the operations. Dahn said, “Running a program like this is a lot of work, and Christopher is very good at what he does and I want to make sure he is compensated in a way so that he stays with us.”

Griggs first came to City Ranch when he was 12 years old and told The Chronicle of the Horse in 2019 that “Every single work skill that I have has come from either my mother or here – mostly here. I’ve learned just about everything I know as far as work etiquette and how to solve problems.” Griggs became a volunteer, then a part-time employee, working his way up to farm manager.

City Ranch now leases a farm and has a full riding and boarding program right at the farm, but that does not stop Dahn and his staff from taking the horses to where they are needed most.

Right before Maryland shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, City Ranch had been working with Michael J. Harrison, DVM, President of the Maryland Horse Breeders Association, to create a horsemanship curriculum for Baltimore City’s public elementary schools. “You know, we have to start with education,” he said, adding, “teaching these kids how to groom a horse could lead them down a path to a career in any part of the horse industry. We are opening up the minds of children through horses.”

Which brings us to Dahn’s solution to… well, basically everything. Education.

Diversifying the Horse Industry

While most of 2020 thus far has been focused on the COVID-19 pandemic, the death of George Floyd under the knee of a police officer in Minneapolis this past May lit a fire across the world. Protesters in nearly every state in the U.S. and in many cities worldwide, began chanting, “Black Lives Matter” and in a way, the world woke up.

“Look, let me tell you a bit about myself,” Dahn said. He went on to explain that he traces his roots to land stolen from his ancestral people, Israelites who were stolen into slavery by the Roman Empire. That heritage fuels his desire to pursue peace and harmony, at home and around the globe, through education and understanding.

“I believe all life on Earth matters but right now, black lives matter and that is what we need to focus on.” Dahn explained his beliefs further by stating, “I believe we are all in this same boat and if the boat sinks, we are going to die together. So I will do my part to keep the boat afloat!”

Dahn pointed out that the current horse community is dominated by fair skinned people and, although one may think this community is all-inclusive, history has proven otherwise. “Let’s look at the black jockeys as an example. Blacks were jockeys when racing got started because it was a dangerous sport,” Dahn explained. “But then racing became more popular and the black jockeys got pushed out. Now seeing a black jockey is very rare.”

Dahn added that over the centuries, people of color have moved farther and farther from the horse industry because they felt like they were not wanted. “The black community isn’t coming [into the sport] because there is a perceived notion that you, the majority race, don’t want us in your space.”

Dahn feels that educating people about stories, such as black jockeys, will help move the industry towards a change. “The horse industry in Maryland needs to advocate for the history of black folks in Maryland’s horse history,” he said. “Who were the black men and women in the horse industry that helped the industry become what it is today? Those are the stories we need to hear more of.”

Dahn also suggests that the Maryland horse industry “advocate to build equestrian facilities where Israelites and Black Americans have access.” He added, “bring the horses to where people of minority live and actively recruit them to join the sport and start riding. We, and I’m speaking now as a member of the Maryland Horse Council, need to get out into the communities of the black and brown people and invite them to join. We have to be proactive if we want to see a change.”

Dahn is fully aware that ending racism is not going to happen over night, saying “it’s a long term journey but look how this [COVID-19] pandemic is driving us closer as a people!”

Transitions

As the economic effects of COVID-19 continue to plague the country and protests continue to drive much needed conversations on racial equality, Dahn admits he often thinks of his son who now lives in Arizona. “He has a very good job out there and really loves the climate. I doubt he’s coming back to Maryland but I keep thinking that I might want to spend the later part of my life out there in his space,” he said.

In order to transition himself into truly being retired, Dahn is looking to set up the program at City Ranch in a way that the people who take it over will “run it and not have to build it.” He is drawing on all of his past life experiences to be sure that City Ranch is set up for success while he also starts moving towards his next dream… “I want to sail to Africa and then travel to Israel. To sail back home.”